|

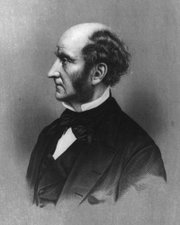

THIS PASSAGE FROM MILL'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY WAS CHOSEN

BOTH FOR CONTENT AND STYLE.

Mill's father James had obtained a measure of fame from works in economics

(influenced by his friend David Ricardo), in psychology, and a history of India. James was also an associate and friend of

Jeremy Bentham, who became John's godfather. Educated by James, John was a child prodigy, who could read and converse in Latin by

the age of five. John made significant contributions in the fields of psychology, logic, ethics, political science,

and economics. He became, without campaigning, an MP for Westminster--but only for one term. The Encarta Encyclopedia says

of John, "His advocacy of women's suffrage in the debate on the Reform Bill of 1867 led to the formation of the suffrage movement."

John died within a year of the birth of his godson Earl Bertrand Russell. This was unfortunate, for Bertrand

was raised by his Victorian dowager aunt. Inspite of--or possible because of--he became quite un-Victorian: an

outspoken atheist and free thinker. He was married 4 times, jailed during WWI for his opposition, a founder

of the British movement opposing nuclear weapons, and during the Vietnam War a leader in opposition thereto. To

disassociate himself from wealth and title he by the age of 30 had given away his entire estate.

All three (Bentham,

John Stuart Mill, and Russell) were child prodigies with a social vision and an activitism which made a difference.

|

|

Seldom

has so much been said in so few words.

Growing Up Without God

Those who admit an omnipotent as well as perfectly just and benevolent maker and ruler

of such a world as this, can say little against Christianity but what can, with at least equal force, be retorted against

themselves. Finding, therefore, no halting place in Deism, he [Mills father] remained in a state of perplexity, until, doubtless

after many struggles, he yielded to the conviction that, concerning the origin of things nothing whatever can be known.

This

is the only correct statement of his opinion; for dogmatic atheism he looked upon as absurd, as most of those, whom the world

has considered Atheists, have always done. These particulars are important, because they show that my fathers rejection of

all that is called religious belief was not, as many might suppose, primarily a matter of logic and evidence; the grounds

of it were moral, still more than intellectual. He found it impossible to believe that a world as full of evil was the work

of an Author combining infinite power with perfect goodness and righteousness. His intellect spurned the subtleties by which

men attempt to blind themselves to this open contradiction....

As it was, his aversion to religion, in the sense usually

attached to the term, was of the same kind as that of Lucretius; he regarded it with the feeling due not a mere mental delusion,

but to a great moral evil. He looked upon it as the greatest enemy of morality; first by setting up factitious excellenciesbelief

in creeds, devotional feelings, and ceremonies, not connected with the good of human kindand causing these to be accepted

as substitutes for genuine virtues; but above all, by radically vitiating the standard of morals, making it consist in doing

the will of a being, on whom it lavishes indeed all the phrases of adulation, but whom in sober truth it depicts as eminently

hateful.

I have a hundred times heard him say that all ages and nations have represented their gods as wicked, in

a constantly increasing progression, that mankind have gone on adding trait after trait till they reached the most perfect

conception of wickedness which the human mind can devise, and have called this God, and prostrated themselves before it. This

ne plus ultra of wickedness he considered to be embodied in what is commonly presented to mankind as the creed of Christianity.

Think (he used to say) of a being who would make a hell-who would create the human race with the infallible foreknowledge,

and therefore with the intention-that the great majority of them were to be consigned to horrible and everlasting torment.

The time, I believe, is drawing near when this dreadful conception of an object of worship will no longer be identified

with Christianity; and when all persons, with any sense of moral good and evil, will look upon it with the same indignation

with which my father regarded it. . . . The world would be astonished if it knew how great a proportion of its brightest ornaments-of

those most distinguished even in popular estimation for wisdom and virtue-are complete skeptics in religion.

A typical

religious person holds fatuous beliefs as truths, including that the world is much stranger than it is, that logic and

science are frequently confuted. As a consequence such a person has limited his ability to understand and act according

to the dictates of reason and is thus more likely to make unsound choices on matters of health, of morals, on personal happiness,

on politics, and in a myriad of other ways. He is a runner with a 20-pound cap

upon his skull: sure, he can run, but but awarkedly—jk.

|