|

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

(1876)

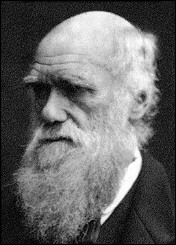

Charles Darwin

Few figures in

Western history evoked, and continue to evoke, such controversy in religious and secular circles as Charles Darwin (1809--1882),

although he himself was an exceptionally mild-mannered individual. Darwin attended the University of Edinburgh and Cambridge,

where he was urged to study science by a professor, I. T Henslow, who secured for him a non-paying post on board the H.M.S.

Beagle. Darwins extensive observations of natural phenomena during the Beagles

voyage to South America established his reputation. His reports were published as Journal

of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle (1839; later known as The Voyage of the Beagle). On this trip, his noticing

of differences within animal species on the Galapagos Islands and in South America led him to begin developing the theory

of evolution by means of natural selection; he had evolved the theory in its essentials as early as 1842, but did not publish

his results until 1859, when On the Origin of Species appeared. That volume and

its successor, The

Descent of Man (1871), revolutionized scientific thought. Darwin himself, however, was reluctant

to become involved in the theological controversies arising out of his theory, leaving that task to his more aggressive

colleague Thomas Henry Huxley. In the last chapter of the Origin Darwin actually

refers to laws of nature having been impressed on matter by the Creator, but in

the end he realized that evolution had both destroyed the argument from design and rendered belief in God doubtful. In his

autobiographypublished in abridged form in his son Francis Darwins edition of his Life and Letters (1888), and in complete form in

1858--Darwin speaks

of the development of his agnostic views.

From Charles Darwin, Autobiography (1876),

in The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, ed.

Francis Darwin, vol. 1 (London: John Murray, 1888), pp. 307-13.

|

|

DURING THESE TWO YEARS [OCTOBER 1936 to January 1839] I was led to think much about religion. Whilst on board the Beagle I was

quite orthodox, and I remember being heartily laughed at by several of the officers (though themselves orthodox) for quoting

the Bible as an unanswerable authority on some point of morality. I suppose it was the novelty of the argument that amused

them. But I had gradually come by this time, i.e., 1836 to 1839, to see that the Old Testament was no more to be trusted

than the sacred books of the Hindoos. The question then continually rose before my mind and would not be banished,--is

it credible that if God were now to make a revelation to the Hindoos, he would permit it to be connected with the belief

in Vishnu, Siva, &c., as Christianity is connected with the Old Testament? This appeared to me utterly incredible.

By further reflecting that the clearest evidence would be requisite to make any sane

man believe in the miracles by which Christianity is supported,--and that the more we know of the fixed laws of nature

the more incredible do miracles become,--that the men at that time were ignorant and credulous to a degree almost incomprehensible

by us,--that the Gospels cannot be proved to have been written simultaneously with the events,that they differ in many important

details, far too important, as it seemed to me, to be admitted as the usual inaccuracies of eye-witnesses;--by such reflections

as these, which I give not as having the least novelty or value, but as they influenced me, I gradually came to disbelieve

in Christianity as a divine revelation. The fact that many false religions have spread over large portions of the earth like

wild-fire had some weight with me.

But I was very unwilling to give up my belief; I feel sure of this, for I can well remember

often and often inventing day-dreams of old letters between distinguished Romans, and manuscripts being discovered at Pompeii

or elsewhere, which confirmed in the most striking manner all that was written in the Gospels. But I found it more and more

difficult, with free scope given to my imagination, to invent evidence which would suffice to convince me. Thus disbelief

crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete. The rate was so slow that I felt no distress.

Although I did not think much about the existence of a personal God until a considerably

later period of my life, I will here give the vague conclusions to which I have been driven. The old argument from design

in Nature, as given by Paley, which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural selection has

been discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made

by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man. There seems to be no more design in the variability of organic

beings, and in the action of natural selection, than in the course which the wind blows. But I have discussed this subject

at the end of my book on the Variation of Domesticated Animals and Plants, and the argument there given has never,

as far as I can see, been answered.

But passing over the endless beautiful adaptations which we everywhere meet with,

it may be asked how can the generally beneficent arrangement of the world be accounted for? Some writers indeed are so much

impressed with the amount of suffering in the world, that they doubt, if we look to all sentient beings, whether there is

more of misery or of happiness; whether the world as a whole is a good or bad one. According to my judgment happiness decidedly

prevails, though this would be very difficult to prove. If the truth of this conclusion be granted, it harmonizes well with

the effects which we might expect from natural selection. If all the individuals of any species were habitually to suffer

to an extreme degree, they would neglect to propagate their kind; but we have no reason to believe that this has ever, or

at least often occurred. Some other considerations, moreover, lead to the belief that all sentient beings have been formed

so as to enjoy, as a general rule, happiness.

Every one who believes, as I do, that all the corporeal and mental organs (excepting those

which are neither advantageous nor disadvantageous to the possessor) of all beings have been developed through natural

selection, or the survival of the fittest, together with use or habit, will admit that these organs have been formed so that

their possessors may compete successfully with other beings, and thus increase in number. Now an animal may be led to

pursue that course of action which is most beneficial to the species by suffering, such as pain, hunger, thirst, and fear;

or by pleasure, as in eating and drinking, and in the propagation of the species, &c.; or by both means combined, as in

the search for food. But pain or suffering of any kind, if long continued, causes depression and lessens the power of

action, yet is well adapted to make a creature guard itself against any great or sudden evil. Pleasurable sensations, on the

other hand, may be long continued without any depressing effect; on the contrary, they stimulate the whole system to increased

action. Hence it has come to pass that most or all sentient beings have been developed in such a manner, through natural selection,

that pleasurable sensations serve as their habitual guides. We see this in the pleasure from exertion, even occasionally from

great exertion of the body or mind,in the pleasure of our daily meals, and especially in the pleasure derived from

sociability, and from loving our families. The sum of such pleasures as these, which are habitual or frequently

recurrent, give, as I can hardly doubt, to most sentient beings an excess of happiness over misery, although many occasionally

suffer much. Such suffering is quite compatible with the belief in Natural Selection, which is not perfect in its action,

but tends only to render each species as successful as possible in the battle for life with other species, in wonderfully

complex and changing circumstances.

That there is much suffering in the world no one disputes. Some have attempted to explain

this with reference to man by imagining that it serves for his moral improvement. But the number of men in the world is as

nothing compared with that of all other sentient beings, and they often suffer greatly without any moral improvement. This

very old argument from the existence of suffering against the existence of an intelligent First Cause seems to me a strong

one; whereas, as just remarked, the presence of much suffering agrees well with the view that all organic beings have

been developed through variation and natural selection.

At the present day the most usual argument for the existence of an intelligent God is

drawn from the deep inward conviction and feelings which are experienced by most persons.

Formerly I was led by feelings such as those just referred to (although I do not

think that the religious sentiment was ever strongly developed in me), to the firm conviction of the existence of God, and

of the immortality of the soul. In my Journal I wrote that whilst standing in the midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian

forest, "it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion, which fill

and elevate the mind." I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the mere breath of his body. But

now the grandest scenes would not cause any such convictions and feelings to rise in m mind. It may be truly said that I am

like a man who has become colour blind, and the universal belief by men of the existence of redness mark ( my present loss

of perception of not the least value as evidence. This argument would be a valid one if all men of all races had the same

inward conviction of the existence of one Cod; but we know that this is very f from being the case. Therefore, I cannot see

that such inward conviction and feelings are of any weight as evidence of what really exists. The state of mind which grand

scenes formerly excited in me, and which was intimately connected with a belief in Cod, did not essentially differ from that

which is often called the sense of sublimity; and however difficult it ma be to explain the genesis of this sense, it can

hardly be advanced as a argument for the existence of God, any more than the powerful though vague and similar feelings excited

by music.

With respect to immortality, nothing shows me [so clearly] how strong and almost

instinctive a belief it is, as the consideration of the view now held by most physicists, namely, that the sun with all the

planets will in time grow too cold for life, unless indeed some great body dashes into the sun, and thus gives it fresh life.

Believing as I do that man in the distant future will be a far more perfect creature than he now is, it is an intolerable

thought that he and all other sentient beings are doomed to complete annihilation after such long-continue slow progress.

To those who fully admit the immortality of the human soul, the destruction of our world will not appear so dreadful.

Another source of conviction in the existence of God, connected with the reason,

and not with the feelings, impresses me as having much more weight. This follows from the extreme difficulty or rather impossibility

of conceiving this immense and wonderful universe including man with his capacity of looking far backwards and far into futurity,

as the result of blind chance or necessity. When thus reflectin I feel compelled to look to a First Cause having an intelligent

mind ii some degree analogous to that of man; and I deserve to be called Theist. This conclusion was strong in my mind about

the time, as far a I can remember, when I wrote the Origin of Species; and it is since that time that it has very gradually,

with many fluctuations, become weaker. But then arises the doubt, can the mind of man, which has, as I full believe, been

developed from a mind as low as that possessed by the lowest animals, be trusted when it draws such grand conclusions?

I cannot pretend to throw the least light on such abstruse problems. The

mystery of the beginning of all things is insoluble by us; and I for one must be content to remain an Agnostic

|